The Socratic vs Pimping Approach to Questioning

In the October 9th installment of Faculty Feed, we put forward the model that telling (alone) is not teaching since learning occurs best when we focus on the extraction of information from the minds of our learners, not merely putting stuff into their heads. Learning can be facilitated by using strategic questioning based on the verb hierarchy in Bloom’s (Bloom, 1956) taxonomy to identify knowledge gaps, surface faulty clinical reasoning, and to encourage the development of critical thinking skills. For learners, it is not answers that drive critical thinking…but questions.

Recently, a young faculty member told me that he liked to use questions to assess what his learners knew and to challenge their thinking, but he didn’t want to “pimp” them. He then asked the question that I suspect is on the minds of many of you…what is the difference between a Socratic line of questioning and pimping? Well, the essential difference between the two can be framed by the intent of the questioner and their ability to create an environment of psychological safety for the learner(s) (Stoddard & O’Dell, 2016).

Intent of the Questioner

Pimping commonly involves asking a learner a series of questions, usually administered in rapid succession. While this approach may serve to motivate, teach, and engage the learner, it can also be interpreted as learner mistreatment. Kost and Chen (2015) define pimping as:

“Questioning with the intent to shame or humiliate the learner to maintain the power hierarchy in medical education.”

Pimping is designed to intimidate the learner, typically with questions that require specific, factual answers, and to determine what the learner knows and doesn’t know. The embarrassment that comes with not knowing does little to enhance learning and pimping is at odds with what we know about how adults learn. Pimping is designed to expose ignorance rather than stimulate new knowledge and can be generated by any faculty member with no preparation.

In contrast, the Socratic method of questioning is learner-centered and is designed to help the learner make connections to prior knowledge and to develop critical thinking skills. This approach questions learners in a systematic and disciplined way by having them analyze, evaluate, interpret, explain and reason their responses through the use of questions directed at fundamental concepts related to principles, theories, and issues, not specific fact-based answers as used in pimping. It takes planning on the part of the instructor to develop a Socratic line of questioning that effectively challenges the completeness and accuracy of their thinking and targets a desirable degree of difficulty for the learner. In the end, the intent of the Socratic type of questioning is to assist, not humiliate the learner (Stoddard & O’Dell, 2016).

Creating a Psychologically Safe Environment for the Learner

The Socratic learner-centric approach to questioning requires a psychologically-safe environment within which to function effectively. So, what does a safe environment look like?

Consider using a designated physical place in which the instructor controls the environment to eliminate distractions and allow time for “pauses” in thinking time required in the Socratic approach to teaching. Within this space, learners must know that they can trust the questioning is not intended to humiliate or intimidate them. If there is no mutual trust and respect between the learner and faculty member, this approach will not be effective. The faculty member should deliberately address this at the beginning of the clinic or rounding session, stating explicitly that he/she will be asking questions to determine just what the learners know, to challenge their assumptions and thought processes, and to probe their understanding of the topic at hand using questions at an appropriate level for the learner. This approach does not mean that we accept substandard performance from learners because accountability is not a tradeoff for psychological safety. “The climate of psychological safety is what differentiates the beauty of Socratic teaching from the counter-educational practice of pimping, and failure to establish psychological safety makes unskillful teachers into “pimpers,” regardless of any attempts to characterize themselves as Socratic” (Stoddard & O’Dell, 2016).

Preparing for a Socratic questioning session

So how do we develop such a line of questioning for use in teaching in a healthcare environment? Given the patients expected to be seen in the clinic or hospital the following day, the faculty member would prepare a series of questions to have available for the learners assigned to him/her. Don’t use questions with yes/no or fact-based answers. Instead, move up Bloom’s Taxonomy and devise questions as Socrates did.

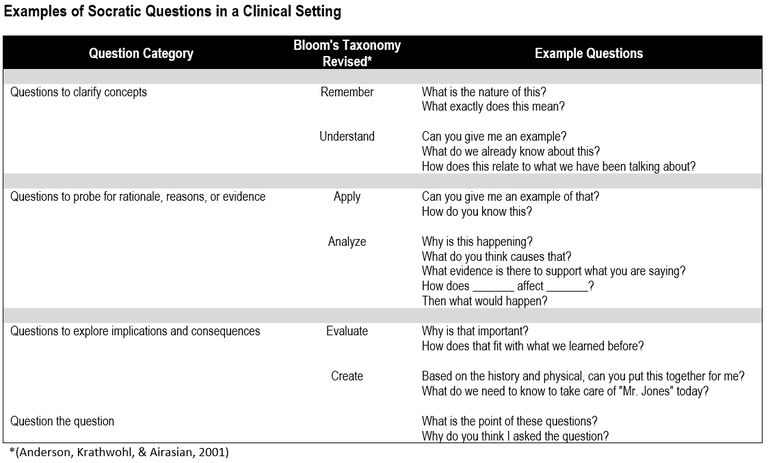

Socrates used questions to:

- clarify concepts

- probe assumptions

- probe rationale, reasons, or evidence

- question viewpoints and perspectives

- probe implications and consequences

- question the question

See the table below for examples of the types of questions from each category:

Socratic questioning is valuable to the learner for two reasons:

1) to identify knowledge gaps, inspiring a genuine passion to fill those gaps thinking more deeply about the answers to these penetrating questions, and

2) to see this approach modeled by their faculty so they can develop their own ability to frame self-directed questions as a foundation for reflection and lifelong learning

For more on Strategic Questioning, we will be releasing Part One and Part Two later this month into the Online Library available through BlackBoard.

Just imagine our impact as educators if we were able to impart on our learners the ability to construct questions for themselves…questions that forced them to clarify concepts, analyze assumptions, question viewpoints, and to probe consequences of the decisions they were learning to make as our next generation of healthcare providers. That, my friends, as Theodore Roosevelt was known to say, is work worth doing.

References

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D., & Airasian, P. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives New York, NY: Longman.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: Handbook I: The cognitive domain. New York, NY: David McKay Co Inc.

Kost, A., & Chen, F. M. (2015). Socrates was not a pimp: Changing the paradigm of questioning in medical education. Academic Medicine, 90(1), 20-24. doi:10.1097/acm.0000000000000446

Stoddard, H. A., & O’Dell, D. V. (2016). Would Socrates Have Actually Used the “Socratic Method” for Clinical Teaching? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(9), 1092-1096. doi:10.1007/s11606-016-3722-2