Telling Is Not Teaching

Before I invoke the ire of the readers by totally dismissing telling as a valuable teaching strategy, perhaps I should acknowledge that a more accurate rendition of this series title should probably be, Telling (alone) is not Teaching. Telling things to learners does have value. It is just that relying solely on this mode of instruction leaves so much to be desired in our roles as educators. Telling is valuable in relating stories that compliment or inform the content we need to get across. Telling is valuable in providing context and an organizational infrastructure within which our learners can hang the details that they discover with our help. Telling has value. It is just not sufficient.

In the September 11, 2019, Faculty Feed post, I recounted my historic teacher-centric approach to teaching and the importance of developing a learner-centric approach because if learning did not occur, we could not claim to have taught. We need to think of good teaching not solely as putting knowledge into our learners’ heads, but rather as the extraction of knowledge from those heads. One of our favorite cognitive scientists focused on learning science says it this way…

How do we do this?...we use questions. Now I am certain that all of us use questions to some extent in the course of clinical and classroom teaching. But when we do use questions, we often ask questions that require only a recitation of facts, and this does little-to-nothing in teaching our learners to think critically, to analyze an issue, or to apply information to solve a problem. We need to get better at asking questions…questions that go deeper, beyond the simple recall of information.

Asking great questions is a core skill for excellent teachers, yet, if you are like me, you never were trained in how to do this. Some of us were fortunate to have worked under a professor who asked great questions, and we emulated their style, but many of us merely had some underlying sense that asking questions was essential. How could we possibly know how important this was if we never were told why and how to do it.

So, why is this important, and just what makes a question great?

Asking great questions does several things that are valuable in the course of helping our learners create new knowledge. Great questions do the following for the learner:

- Identify knowledge gaps (which helps faculty too)

- Stimulate the learner to retrieve knowledge

- Establish a culture of curiosity

- Improve critical thinking skills

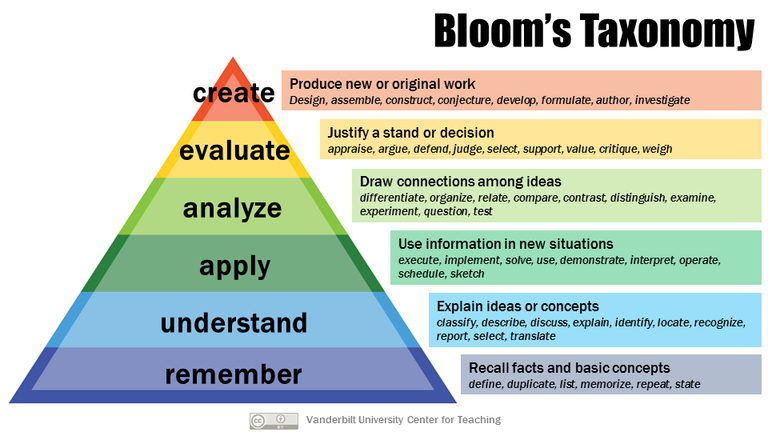

Asking great questions is facilitated by using something called Bloom’s Taxonomy, a tool initially developed in 1956 as a curriculum-development tool, but that has also been applied to writing learning objectives and can also be used to develop effective questions (Bloom).

The diagram below is the updated version of the taxonomy that was completed in 2001 (Anderson, Krathwohl, & Airasian).

We use Bloom’s Taxonomy’s hierarchy of verbs to structure questions that are designed to elicit a range of responses from our learners. When we use verbs from the lowest levels of the taxonomy, we are asking lower-order questions (remember, understand), that primarily seek a recitation of facts. When we ask questions using verbs from the top half of the hierarchy, we are asking higher-order questions (apply, analyze, evaluate, create) that require the learner to do more than retrieve factual information from their memory. Asking higher-order questions forces the learner to use the factual information they have in their head to make connections, synthesize information and formulate a response…in essence, to think. This is especially important if we are to meet the mandate of our health sciences schools’ accrediting bodies to teach our learners critical-thinking and lifelong-learning skills.

The HSC faculty development team has created a two-part module (Strategic Questioning Parts I and II) that will become part of the HSC Faculty Development online library this month. Check these out for a more detailed and interactive dive into the “how to” skill of asking better questions. In our next two installments, we will comment on strategic questioning versus pimping, and the importance of granting think time to your learner after you ask a question in order to allow the learner to process a response.

The role we have as educators of the next generation of nurses, doctors, dentists, and public health officials magnifies our individual patient care efforts. Let’s make the most of this vital responsibility and commit to asking great questions. Just imagine the impact we could have if all 1,004 faculty on the UofL HSC campus asked just one great question of our learners this week….and the next week and the week after. What a powerful force for excellent teaching that would be.

References

Anderson, L. W., Krathwohl, D., & Airasian, P. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom's taxonomy of educational objectives New York, NY: Longman.

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: Handbook I: The cognitive domain. New York, NY: David McKay Co Inc.