Spaced Retrieval: Strengthening the Durable Memory

Last week, we introduced you to the practice of retrieval as described in the book, Make it Stick (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014), and to the notion that our brains are like a forest with memories that we need to extract in order to create durable memory. That process of retrieval makes a clearer path to find it, and helps to defeat the inevitable loss of what we have “learned” as illustrated in the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve we showed you in last week’s blog. So if retrieving the memory once results in better retention of what we have learned, how about repeated efforts at retrieval? Does that result in a more durable memory? Is there evidence as to how best to do that repeated retrieval? Well, it turns out that there is evidence to support it. Let’s expand on retrieval and tee up the idea of spaced retrieval.

Spaced retrieval as a study strategy is generally not recognized by most of us as a useful study approach. We generally default to what we have always used…re-reading and cramming for tests (the cognitive scientists call this massed study). These approaches are far less effective when compared to spaced retrieval. So just what does spaced retrieval do to enhance the process of learning? In chapter 2 of Make it Stick (Brown et al., 2014), the authors cite empirical research that retrieval makes learning stick far better than re-exposure to the original material. They go on to point out that for retrieval to be most effective, it must be repeated again and again in “spaced-out sessions so that recall, rather than becoming a mindless recitation, requires some cognitive effort” (2014, p. 28). Spacing out the retrieval allows some forgetting to occur between retrieval efforts, resulting in the need for more cognitive effort to make the retrieval and more work equals learning.

Forgetting is good for learning (Bjork & Bjork, 2019). Creating conditions that facilitate forgetting, like spacing out the time between retrieval efforts, or interleaving the content to be reviewed/retrieved results in more durable memory. Cognitive psychologists call this power of retrieval the testing effect or the retrieval-practice effect. Retrieval is essentially a form of quizzing. Faculty can strategically quiz their learners or learners can quiz themselves. With either approach, quizzing is better than re-reading or cramming if the goal is long-term retention. And being quizzed at intervals long enough to allow for some forgetting to occur is a valuable approach.

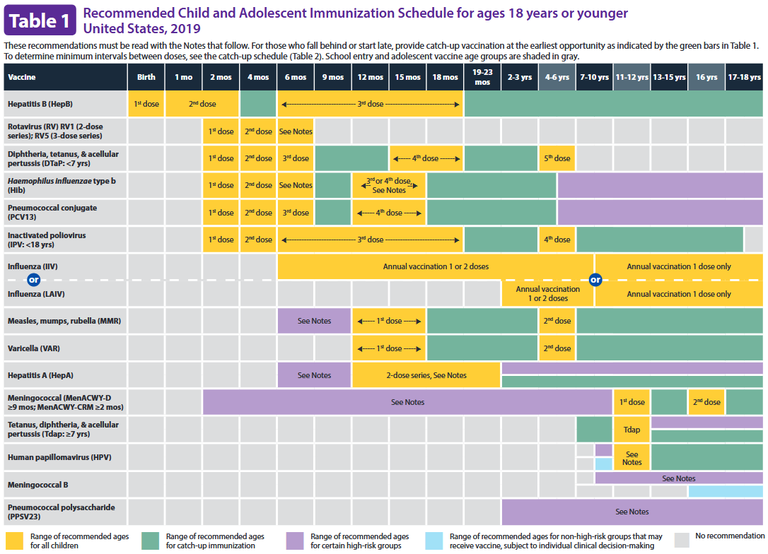

As I came to understand the value of spaced retrieval on memory retention in our brains, I recalled another use of spacing to achieve long-term memory… the spacing of childhood immunizations with booster doses of vaccine to achieve better long-term immunologic memory. So, let’s review a bit of vaccine immunology and take a look at the childhood vaccine schedule. Essentially, vaccines (whether bacterial or viral, live or inactivated) present the child’s immune system with antigens. These antigens are presented to lymphocytes triggering an immunologic response that results in the production of antibodies specific to the antigen (humoral immunity) and a cellular immune response as well (cellular immunity). We know that for the child to develop long-lasting immunologic memory to this antigenic stimulation, that the immune system needs to be challenged more than once. For some vaccines, two doses is sufficient (Measles, Mumps, Rubella) and for others, up to five doses are required to get the optimal, long-lasting immune response (Diphtheria, Pertussis, Tetanus). In addition to the number of doses of vaccine, clinical trials have defined that there are specific spacing intervals that result in optimal vaccine immunogenicity. The booster causes the immune system to “remember” having seen the antigen before and initiates a cascade of responses that result in better immunologic memory for the bacterial or viral antigen in the vaccine. As an illustration of this approach, see the 2019 CDC recommended vaccine schedule for details.

Table 1: Recommended Child and Adolescent Immunization Schedule for ages 18 years or younger, United States, 2019, CDC

Our brains and our immune systems seem to have some things in common, at least in terms of how durable memory is created. Just as repeated spaced retrieval helps us have better long-term memory for things we have learned, our immunologic memory for bacterial and viral antigens is more durable if we can get our immune system to "remember" having seen those antigens through a system of spaced administration of those antigens. There is an incredible parallel between how the brain learns and how our immune system learns.

Key points to take-away:

- If you are trying to learn something and not forget it, find a way to use spaced retrieval to build a stronger connection to the memory in the forest of your brain.

- If you are responsible for teaching others, tell them of this phenomenon so they can self-quiz, and build in a way to repeatedly test your learners using quizzing (verbal or written) as a form of retrieval to help them develop durable memory.

References

Bjork, R. A., & Bjork, E. L. (2019). Forgetting as the friend of learning: Implications for teaching and self-regulated learning. Advances in physiology education, 43(2), 164-167. doi:10.1152/advan.00001.2019

Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L. I., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.