Is Learning Magical?

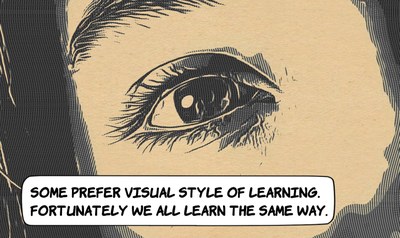

It was not until several years later, however, that I found out that I was not actually an auditory learner. I perceived myself as an auditory learner. But I wasn’t a visual learner, a reading-writing learner, or a kinesthetic learner either. In fact, I am all of these, and you and your learners are too. To state this as simply as possible: there is no evidence to support learning styles. Learning styles are a myth that keeps rearing its ugly head. We all have learning preferences or a way that we perceive we like to learn. But the best way to learn is multi-modal, or a combination of modalities with the learner actually doing something with the information in their head.

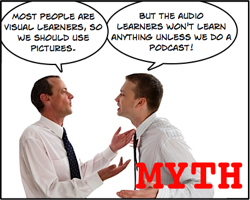

It was not until several years later, however, that I found out that I was not actually an auditory learner. I perceived myself as an auditory learner. But I wasn’t a visual learner, a reading-writing learner, or a kinesthetic learner either. In fact, I am all of these, and you and your learners are too. To state this as simply as possible: there is no evidence to support learning styles. Learning styles are a myth that keeps rearing its ugly head. We all have learning preferences or a way that we perceive we like to learn. But the best way to learn is multi-modal, or a combination of modalities with the learner actually doing something with the information in their head.  In fact, a 2019 article from the American Psychological Association reported that 90% of the 668 participants in one study–including educators—believed that people learn best when they are taught in their “predominate” learning style. To say this myth is widespread is an understatement. Since we know that many of our learners think that their learning depends on the educator’s use of teaching strategies that match their preferred learning style, what can we do?

In fact, a 2019 article from the American Psychological Association reported that 90% of the 668 participants in one study–including educators—believed that people learn best when they are taught in their “predominate” learning style. To say this myth is widespread is an understatement. Since we know that many of our learners think that their learning depends on the educator’s use of teaching strategies that match their preferred learning style, what can we do?

Fortunately, cognitive scientists have identified many methods to enhance knowledge acquisition, and these techniques have universal benefits. Students are more successful when they space out their study over time, experience the material in multiple modalities, test themselves on the material as part of their study practices, and learner elaboration on material to make meaningful connections rather than engaging in activities that involve simple repetition of information (e.g., making flashcards or recopying notes). These effective strategies were identified decades ago and have convincing and significant empirical support. Why then, do we persist in our belief that learning styles matter, and ignore these tried-and-true techniques?

It is human nature to create understandings by using categories, and some cognitive psychologists suggest that learning styles have taken hold due to the way it gives us simple, specific categories to use and understand. The popularity of the learning styles mythology may also stem in part from the appeal of finding out what “type of person” you are, along with the desire to be treated as an individual within the education system. In contrast, the notion that universal, multi-modal strategies may enhance learning for all contradicts the general notion that humans are distinctive in how they learn.

It is human nature to create understandings by using categories, and some cognitive psychologists suggest that learning styles have taken hold due to the way it gives us simple, specific categories to use and understand. The popularity of the learning styles mythology may also stem in part from the appeal of finding out what “type of person” you are, along with the desire to be treated as an individual within the education system. In contrast, the notion that universal, multi-modal strategies may enhance learning for all contradicts the general notion that humans are distinctive in how they learn. Additional References:

Nancekivell, S. E., Shah, P., & Gelman, S. A. (2020). Maybe they’re born with it, or maybe it’s experience: Toward a deeper understanding of the learning style myth. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112(2), 221.

American Psychological Association. (2019, May 29). Belief in learning styles myth may be detrimental [Press release]. http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2019/05/learning-styles-myth