Creating A Durable Memory

I must admit to some surprise at just how much interest there has been among HSC faculty for the book, Make It Stick (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014). Since we introduced this book to the HSC faculty this past spring as a reading circle, the interest in this book has exploded. We have been asked to present multiple workshops for faculty and residents, and by the end of the 2019 calendar year, we will have had nearly 50 faculty from across the HSC campus participate in Reading Circles for this book.

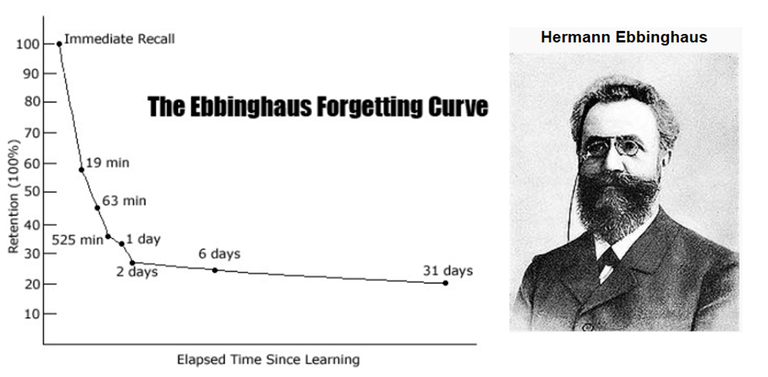

Perhaps I shouldn’t be surprised. Who among us has a memory that is as strong as we would like it to be? I forget stuff that I have “learned” all the time. We all do. The Ebbinghaus forgetting curve reminds us of just how quickly we lose it.

Figure 1. Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve. (Original work published 1885)

Don’t we want to retain what we learn, since none of us has time to re-learn or re-read what we are already supposed to know? There has just got to be a better way.

Well, it turns out that there is a better way, and Make it Stick neatly outlines the evidence in support of the study strategies that really work. One of the principal strategies this book highlights is the practice of retrieval, so let’s spend a bit of time unpacking what retrieval is and how it works.

Retrieval is “self-quizzing”, or a focus more on getting information out of students’ heads than putting information into students’ heads. Retrieval is more work than the most frequently-used study strategy…re-reading. We all use re-reading as our go-to study approach because it is easier than repeatedly asking yourself questions like these:

What did I just read?

What were the key ideas presented?

How can I connect this information to what I already know?

Learning occurs when there is some desirable difficulty with the process, and self-quizzing is definitely harder than re-reading. But is it really better than re-reading?

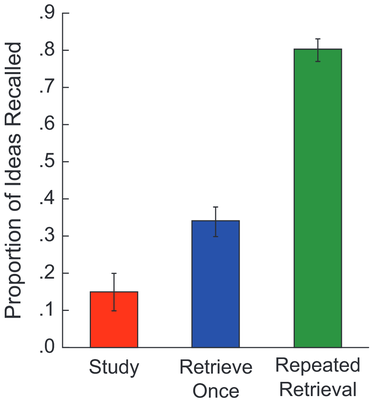

Take a look at some research results from a publication by Jeff Karpicke (Karpicke, 2012).

Figure 2. Long-term retention and retrieval (from Karpicke, 2012)

Figure 2 shows the proportion of ideas recalled one week after first learning the content. By using active retrieval just one time, the learner doubled their retention compared to the group that only reread (“study”). How many of our students, residents, fellows, and ourselves spend a significant amount of time rereading content, all the content, trying to stuff it into our brains. If we only practiced pulling it out of our brains regularly, we all would be much better off.

So active retrieval is better…but why is active retrieval better than only re-reading?

In Make it Stick, the authors cite the story of a biology professor from the University of Washington, Mary Pat Wentworth. She models retrieval with her students to help them understand how to do it. Here is how she describes the process:

“Every five minutes or so, (during a lecture) I throw out a question on the material we just talked about, and I can see them start to look through their notes. I say, stop. Do not look at your notes. Just take a minute to think about it yourself.

tell them our brains are like a forest, and your memory is in there somewhere. You’re here, and the memory is over there. The more times you make a path to that memory, the better the path is, so that the next time you need the memory, it’s going to be easier to find it. But as soon as you get your notes out, you have short-circuited the path. You are not exploring the path anymore, someone has told you the way.”

This approach of deliberately bringing memories to mind, making a path to the memory, boosts learning. Also, the more difficult the retrieval practice, the better the learning is. There is a basis for this claim in neuroscience. This process results in more myelination of the nerves connecting to that memory. Recall that myelination allows rapid and reliable propagation of action potentials over long distances in the nervous system. Active retrieval practice builds up the myelin sheath, allowing action potentials to propagate along an axon in a saltatory fashion with higher speed making a better path to the memory in the forest of your brain.

None of us has time to learn inefficiently. For those of you who have not become familiar with the book, Make it Stick, we recommend that you read it (or join the next HSC reading circle) to better understand how to use retrieval, elaboration, interleaving, and the other strategies described. As professional healthcare educators, we owe it to ourselves, and more importantly, we owe it to our learners to teach them how to create durable memory and to help them become lifelong learners.

References:

Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L. I., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick: The science of successful learning. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1964). Memory (H. A. Ruger & Bussenius, C. E.). New York, NY: Dover. (Original work published 1885)

Karpicke, J., D. (2012). Retrieval-based learning: Active retrieval promotes meaningful learning. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(3), 157-163.