75 Years of Beautiful Music

The School of Music Celebrates Noteworthy Milestone

---By Kevin Rayburn

One fine day in November 1959, one of the greatest composers of the 20th century stopped by for lunch at the University of Louisville School of Music.

One fine day in November 1959, one of the greatest composers of the 20th century stopped by for lunch at the University of Louisville School of Music.

Dmitri Shostakovich, the leading musical figure of the Soviet Union, was in Louisville as part of a goodwill tour with five other Soviet musical artists at the height of the Cold War. The Louisville Orchestra and guest pianist Eugene List performed his fiery first piano concerto the next night.

Shostakovich was polite but morose, spoke little, nervously drummed his hands together and his brow a lot, smoked incessantly and drank coffee—and earlier in the day, some scotch.

Evidence of Shostakovich’s visit can be seen in photographs of him and prominent fellow composer Dmitri Kabalevsky displayed in the school’s Dwight Anderson Music Library.

Proof that UofL had become a locus of musical life, not just locally but internationally, also can be seen in another of the music library’s unique treasures: a guestbook containing the signatures of hundreds of dignitaries who’ve visited or performed at the school since 1948.

Shostakovich’s signature is in it, and so are those of other major composers such as Aaron Copland, Virgil Thomson, Roy Harris, Paul Hindemith, Roger Sessions and Vincent Persichetti, as well as Witold Lutoslawski and all of the other winners of the Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition.

Also leaving their marks were jazz greats Dave Brubeck and Wynton Marsalis and members of leading chamber ensembles including the Takács, Juilliard, Emerson and Beaux Arts quartets.

The book also contains the signature William Schwann, 1935 music graduate and founder of the leading catalog of classical music recordings for many decades, the Schwann Record and Tape Guide (later the Schwann Compact Disc Catalog).

Yet, the school that for 75 years educated Schwann and thousands of other music students, that attracted prominent visiting musical artists and that has served as the home for lively student ensembles and creative faculty almost didn’t happen.

A Shoestring Experiment

in the Depression

The financial collapse of the proprietary Louisville Conservatory of Music during the dark days of the Great Depression in the early 1930s threatened to create a vacuum in music education in the city.

At that time, UofL only had a part-time department of music that offered courses in theory, history and performance—but no degree.

UofL President Raymond Kent and the board of trustees, aware of the university’s responsibility to provide an alternative, sought the Juilliard Foundation’s advice about merging with the conservatory.

With advisers that included Juilliard’s President John Erskine and Madame Samaroff Stokowski (second wife of the famous conductor Leopold Stokowski), the foundation agreed that UofL’s merger with the conservatory was feasible and worthy of its support. Juilliard sent pianist Jacques Jolas to UofL to serve as the School of Music’s first dean. With the school’s founding in 1932 came a proviso from UofL administration: The new school had three years to wean itself off Juilliard support and become self-supporting. If it bled money like the conservatory had, it would cease to be.

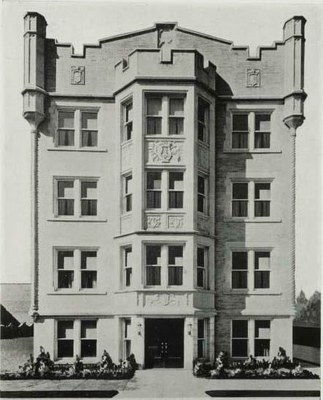

The defunct conservatory provided most of the school’s initial 60 students and 18 faculty members. It opened in the old conservatory building at 720 South Brook Street (near what is nowUofL’s Health Sciences Center campus) on Nov. 21, 1932.

The defunct conservatory provided most of the school’s initial 60 students and 18 faculty members. It opened in the old conservatory building at 720 South Brook Street (near what is nowUofL’s Health Sciences Center campus) on Nov. 21, 1932.

Jolas declared the school’s mission was “to train in every phase of music; to train the performer, the teacher, the serious amateur… the all-around musician.”

Despite facilities that sported only one upright piano, the enthusiasm of the faculty and students as well as Jolas’ sturdy leadership made the school a success.

That growing success was recognized in 1933 when U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis donated funds to help start a music library at the school. The next year, the Carnegie Library donated what was then a small fortune, $4,000 worth of accessories and recordings for stocking a library, including musical scores and books, a $650 electric phonograph and a complete set of recordings of Ludwig van Beethoven’s nine symphonies.

The culmination of the fledgling school’s triumphs was its first accreditation by the National Association of Schools of Music in 1936.

After the departure of Jolas in 1935, the school appointed former conservatory pianist Dwight Anderson as dean. Anderson’s 19-year tenure, from 1937 to 1956, was the longest in the school’s history. His name now adorns the school’s library.

In a 1983 story in UofL magazine, music graduate Richard Spalding reminisced about the school under Anderson’s influential leadership.

“We had fabulous teachers, really superb artists,” he said. “Dean Anderson was a very strong musician. He had been a concert pianist. In fact, people called it a piano school because he had so many students. He set the tone.”

Back then, Spalding recalled, faculty and students were very close in a shared love of music and learning, and invited each other to their homes to make music or participate in social functions. Anderson also encouraged students to get out into the world, to travel to other cities to experience major orchestras and performers. That’s partly because Louisville, as of 1937, did not have an orchestra of its own.

That changed dramatically that year when conductor Robert Whitney and Louisville Mayor Charles Farnsley founded the Louisville Orchestra. In subsequent years UofL’s ties to the orchestra and other ensembles in Louisville became symbiotic and essential to the city’s cultural life.

The music school’s stature increased in 1937 with the recruitment of music history scholar Gerhard Herz, who remained a fixture at the school for decades.

Herz’s presence made UofL one of the leading centers in the study of the works of Johann Sebastian Bach, whom Herz described as “the greatest phenomenon in music history.”

A Music School on the

A Music School on the

Move—Literally

Like a M*A*S*H unit, the growing school had to pull up stakes often, residing in a series of inadequate facilities during its first 15 years.

But in April 1947, the school moved into a home worthy of its noble mission. Gardencourt, as it was called, was a regal mansion sitting on 14 verdant acres near Louisville’s Cherokee Park. The heirs of Mattie Norton donated it to UofL.

Buses would convey students back and forth from Belknap campus to Gardencourt.

For many, Gardencourt’s two decades as the school’s home represented a kind of golden age.

The late Clarita Whitney, wife of the Louisville Orchestra conductor and longtime UofL employee, remembered her days serving there in the 1950s as Dean Anderson’s assistant.

In a 1987 story she wrote for Inside UofL, Whitney recalled Gardencourt as a “lovely treasure…conducive to serious music study.

treasure…conducive to serious music study.

“I can still hear the students practicing their instruments under the trees in the spring, the hundreds of recitals and concerts in the great gold room, the beautiful singing from a voice studio above my office and the annual Eine Kleine Nachtmusik garden concerts in the spring.”

It was there that Shostakovich, Copland and others were welcomed to Louisville.

Even so, Gardencourt eventually became inadequate for the school’s growing needs and was closed in 1969. Again, the school found itself shuffled into a series of makeshift homes for several years.

Essential to Louisville’s Musical Life

Robert Whitney had led the Louisville Orchestra for almost 20 years when he became the school’s dean in 1956. He remained the orchestra’s director for many years thereafter and served as music dean until 1971.

became the school’s dean in 1956. He remained the orchestra’s director for many years thereafter and served as music dean until 1971.

Whitney’s legacy of championing new composers and recording challenging 20th-century music with the orchestra was one that has been shared through the years with UofL.

A 1950s music school brochure made no bones about the school’s key role in Louisville’s cultural scene, declaring it to be “the focus of the musical life of the city.”

That was evident early in Dean Anderson’s tenure when he, philanthropist Morris Belknap and Herz formed the Chamber Music Society of Louisville in 1938. That community group has been affiliated with UofL ever since.

A lack of grand opera in Louisville led to a similar effort in 1949 when the school recruited New York opera director Moritz von Bomhard to run an opera workshop program that soon became the Kentucky Opera Association. To this day, UofL music students participate in its performances.

Another notable event was the 1964 founding of the Louisville Bach Society by UofL’s Melvin Dickinson (now emeritus music professor).

Wherever there is a musical ensemble in Louisville, large or small, it is likely that many or most of its members are students, graduates or faculty of UofL.

Fans of UofL sports know the school largely from its marching band, which traces its roots to the 1920s. Through the 1940s and 1950s the “Marching Cardinals” treated university football fans to well-choreographed halftime shows and achieved some fame when one of its majorettes, Hilda Gay Mayberry, was named best in the nation.

Budgetary woes ended the band in 1970, with a pep band filling the void until 1979, when the marching band was reorganized. It has been the official Kentucky Derby band since 1980, and some years prior to that. TV viewers yearly around the world hear the band’s rendition of “My Old Kentucky Home” before the race.

With engagements such as their recent appearance during the Cardinal football team’s winning Orange Bowl game and with the continued support of generous supporters such as Owsley Brown Frazier, the UofL Marching Band’s future looks good.

Toward a New Era

Louisvillians Bernice Williams and Leandrew Green stood in front of a table in a photograph published in the Sept. 12, 1950, edition of the Courier-Journal. The photo and small headline caption modestly marked a milestone for the school, one that was emblematic of broader social change. It read: “Negro Students Enroll for First Time in UofL’s School of Music.”

Along with a more diverse student body, the school proudly cited the accomplishments of its graduates as it headed into the 1960s. In one of its publications of the period the school noted that its hundreds of graduates had entered into every kind of musical profession: as performers, teachers at all educational levels, church musicians, concert artists, agents, conductors, critics, publishers, administrators, therapists and librarians.

Jolas’ comprehensive educational vision for the school, uttered 30 years prior, had come to pass.

But something else from the past re-emerged, too: impermanent or inadequate facilities, which again plagued the school from 1969 to 1980. Classes took place between rundown sites at Belknap campus and in the facilities of the former Kentucky Southern College buildings on UofL’s Shelby campus.

That too would change for the better.

That too would change for the better.

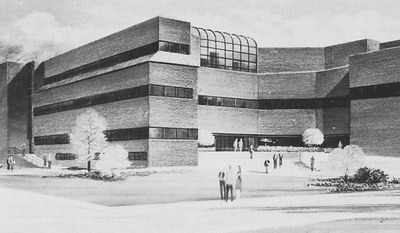

The major triumph of then-President James Grier Miller and Dean Jerry Ball, who ran the school from 1971 to 1990, was also a first in the school’s history. The new School of Music building, opened in 1980, was the first facility built specifically for music education at UofL. Students, faculty and performing groups finally had a proper space for their needs.

Since then, the school has had many milestones under Ball and subsequent deans Paul Brink (1990–1992, acting), Herbert Koerselman (1992–2002) and Christopher Doane (2002–present). A few of them have included:

- UofL becoming host site of the Jamey Aebersold Summer workshop in 1977. The introduction of jazz courses at UofL would lead to the establishment of the Jamey Aebersold Jazz Studies program in 1985 through 2021 and the recruitment of prominent jazz faculty, including trumpeter, composer educator and Grammy Award nominee John La Barbera.

- Awarding of the first Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition to Witold Lutoslawski in 1985. In its subsequent two decades, the award has become recognized internationally as one of the top prizes for musical creativity as well as being the most lucrative.

- Awarding of the first Grawemeyer Award for Music Composition to Witold Lutoslawski in 1985. In its subsequent two decades, the award has become recognized internationally as one of the top prizes for musical creativity as well as being the most lucrative.

- Expansion of opera at UofL in 1997 with the appointment of Kimcherie Lloyd as the Bomhard Music Theatre Chair and director of the opera program. Her 1999 appointment as music director of the Kentucky Opera Association solidified the strong ties between UofL and the Louisville arts community.

- Establishment of the music therapy program in 2000.

- Growth of the Dwight Anderson Music Library and upgrades to improve amenities and access to its collections of 100,000 volumes, 22,000 discs, special collections and other resources.

- Enhancement of UofL’s growing international efforts with establishment of an ongoing relationship with the Karol Szymanowski Academy of Music in Katowice, Poland, and programs in Japan, Russia, Brazil, Argentina and Barbados.

- Increasing recognition and top-prize awards for UofL’s choral ensembles in the mid-2000’s, as well as the designation of all of the school’s ensembles as A Program of National Excellence at UofL.

“We celebrate a rich history in our school’s 75th year,” says Dean Doane. “And it’s exciting to realize that—on so many fronts—we’re writing dynamic new chapters to that story.”

For more information on the school and UofL history, go to:

UofL Archives and Special Collections library.louisville.edu/archives/home