Chapter IX: The Failure of Banker-Management

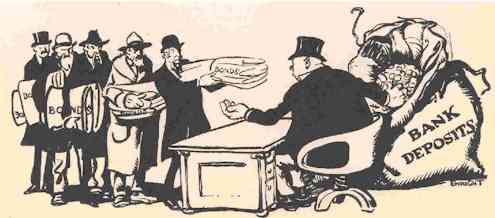

Illustration from Harper's Weekly December 27, 1913 by Walter J. Enright

Thereis not one moral, but many, to be drawn from the Decline of the New Haven and the Fall of Mellen. That history offers texts for many sermons. It illustrates the Evils of Monopoly, the Curse of Bigness, the Futility of Lying, and the Pitfalls of Law-Breaking. But perhaps the most impressive lesson that it should teach to investors is the failure of banker-management.

Banker Control

For years J. P. Morgan & Co. were the fiscal agents of the New Haven. For years Mr. Morgan wasthedirector of the Company. He gave to that property probably closer personal attention than to any other of his many interests. Stockholders' meetings are rarely interesting or important; and few indeed must have been the occasions when Mr. Morgan attended any stockholders' meeting of other companies in which he was a director. But it was his habit, when in America, to be present at meetings of the New Haven. In 1907, when the policy of monopolistic expansion was first challenged, and again at the meeting in 1909 (after Massachusetts had unwisely accorded its sanction to the Boston & Maine merger), Mr. Morgan himself moved the large increases of stock which were unanimously voted. Of course, he attended the important directors' meeting. His will was law. President Mellen indicated this in his statement before Interstate Commerce Commissioner Prouty, while discussing the New York, Westchester & Boston—the railroad without a terminal in New York, which cost the New Haven $1,500,000 a mile to acquire, and was then costing it, in operating deficits and interest charges, $100,000 a month to run:

"I am in a very embarrassing position, Mr. Commissioner, regarding the New York, Westchester & Boston. I have never been enthusiastic or at all optimistic of its being a good investment for our company in the present, or in the immediate future; but people in whom I had greater confidence than I have in myself thought it was wise and desirable; I yielded my judgment; indeed, I don't know that it would have made much difference whether I yielded or not."

The Banker's Responsibility

Bankers are credited with being a conservative force in the community. The tradition lingers that they are preeminently "safe and sane." And yet, the most grievous fault of this banker-managed railroad has been its financial recklessness—a fault that has already brought heavy losses to many thousands of small investors throughout New England for whom bankers are supposed to be natural guardians. In a community where its railroad stocks have for generations been deemed absolutely safe investments, the passing of the New Haven and of the Boston & Maine dividends after an unbroken dividend record of generations comes as a disaster.

This disaster is due mainly to enterprises outside the legitimate operation of these railroads; for no railroad company has equaled the New Haven in the quantity and extravagance of its outside enterprises. But it must be remembered, that neither the president of the New Haven nor any other railroad manager could engage in such transactions without the sanction of the Board of Directors. It is the directors, not Mr. Mellen, who should bear the responsibility.

Close scrutiny of the transactions discloses no justification. On the contrary, scrutiny serves only to make more clear the gravity of the errors committed. Not merely were recklessly extravagant acquisitions made in mad pursuit of monopoly; but the financial judgment, the financiering itself, was conspicuously bad. To pay for property several times what it is worth, to engage in grossly unwise enterprises, are errors of which no conservative directors should be found guilty; for perhaps the most important function of directors is to test the conclusions and curb by calm counsel the excessive zeal of too ambitious managers. But while we have no right to expect from bankers exceptionally good judgment in ordinary business matters; we do have a right to expect from them prudence, reasonably good financiering, and insistence upon straightforward accounting. And it is just the lack of these qualities in the New Haven management to which the severe criticism of the Interstate Commerce Commission is particularly directed.

Commissioner Prouty calls attention to the vast increase of capitalization. During the nine years beginning July 1, 1903, the capital of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad Company itself increased from $93,000,000 to about $417,000,000 (excluding premiums). That fact alone would not convict the management of reckless financiering ; but the fact that so little of the new capital was represented by stock might well raise a question as to its conservativeness. For the indebtedness (including guaranties) was increased over twenty times (from about $14,000,000 to $300,000,000), while the stock outstanding in the hands of the public was not doubled ($80,000,000 to $158,000,000). Still, in these days of large things, even such growth of corporate liabilities might be consistent with "safe and sane management."

But what can be said in defense of the financial judgment of the banker-management under which these two railroads find themselves confronted, in the fateful year 1913, with a most disquieting floating indebtedness? On March 31, the New Haven had outstanding $43,000,000 in short-time notes; the Boston & Maine had then outstanding $24,500,000, which have been increased since to $27,000,000; and additional notes have been issued by several of its subsidiary lines. Mainly to meet its share of these loans, the New Haven, which before its great expansion could sell at par 3 1/2 per cent. bonds convertible into stock at $150 a share, was so eager to issue at par $67,500,000 of its 6 per cent. 20-year bonds convertible into stock as to agree to pay J. P. Morgan & Co. a 2 1/2 per cent. underwriting commission. True, money was "tight" then. But is it not very bad financiering to be so unprepared for the "tight" money market which had been long expected? Indeed, the New Haven's management, particularly, ought to have avoided such an error; for it committed a similar one in the "tight" money market of 1907-1908, when it had to sell at par $39,000,000 of its 6 per cent. 40-year bonds.

These huge short-time borrowings of the System were not due to unexpected emergencies or to their monetary conditions. They were of gradual growth. On June 30, 1910, the two companies owed in short-term notes only $10,180,364; by June 30, 1911, the amount had grown to $30,759,959; by June 30, 1912, to $45,395,000; and in 1913 to over $70,000,000. Of course the rate of interest on the loans increased also very largely. And these loans were incurred unnecessarily. They represent, in the main, not improvements on the New Haven or on the Boston & Maine Railroads, but money borrowed either to pay for stocks in other companies which these companies could not afford to buy, or to pay dividends which had not been earned.

In five years out of the last six the New Haven Railroad has, on its own showing, paid dividends in excess of the year's earnings; and the annual deficits disclosed would have been much larger if proper charges for depreciation of equipment and of steamships had been made. In each of the last three years, during which the New Haven had absolute control of the Boston & Maine, the latter paid out in dividends so much in excess of earnings that before April, 1913, the surplus accumulated in earlier years had been converted into a deficit.

Surely these facts show, at least, an extraordinary lack of financial prudence.

Why Banker-Management Failed

Now, how can the failure of the banker-management of the New Haven be explained?

A few have questioned the ability; a few the integrity of the bankers. Commissioner Prouty attributed the mistakes made to the Company's pursuit of a transportation monopoly.

"The reason," says he, "is as apparent as the fact itself. The present management of that Company started out with the purpose of controlling the transportation facilities of New England. In the accomplishment of that purpose it bought what must be had and paid what must be paid. To this purpose and its attempted execution can be traced every one of these financial misfortunes and derelictions."

But it still remains to find the cause of the bad judgment exercised by the eminent banker-management in entering upon and in carrying out the policy of monopoly. For there were as grave errors in the execution of the policy of monopoly as in its adoption. Indeed, it was the aggregation of important errors of detail which compelled first the reduction, then the passing of dividends and which ultimately impaired the Company's credit.

The failure of the banker-management of the New Haven cannot be explained as the shortcomings of individuals. The failure was not accidental. It was not exceptional. It was the natural result of confusing the functions of banker and business man.

Undivided Loyalty

The banker should be detached from the business for which he performs the banking service. This detachment is desirable, in the first place, in order to avoid conflict of interest. The relation of banker-directors to corporations which they finance has been a subject of just criticism. Their conflicting interests necessarily prevent single-minded devotion to the corporation. When a banker-director of a railroad decides as railroad man that it shall issue securities, and then sells them to himself as banker, fixing the price at which they are to be taken, there is necessarily grave danger that the interests of the railroad may suffer—suffer both through issuing of securities which ought not to be issued, and from selling them at a price less favorable to the company than should have been obtained. For it is ordinarily impossible for a banker-director to judge impartially between the corporation and himself. Even if he succeeded in being impartial, the relation would not conduce to the best interests of the company. The best bargains are made when buyer and seller are represented by different persons.

Detachment an Essential

But the objection to banker-management does not rest wholly, or perhaps mainly, upon the importance of avoiding divided loyalty. A complete detachment of the banker from the corporation is necessary in order to secure for the railroad the benefit of the clearest financial judgment; for the banker's judgment will be necessarily clouded by participation in the management or by ultimate responsibility for the policy actually pursued. It isoutsidefinancial advice which the railroad needs.

Long ago it was recognized that "a man who is his own lawyer has a fool for a client." The essential reason for this is that soundness of judgment is easily obscured by self-interest. Similarly, it is not the proper function of the banker to construct, purchase, or operate railroads, or to engage in industrial enterprises. The proper function of the banker is to give to or to withhold credit from other concerns; to purchase or to refuse to purchase securities from other concerns; and to sell securities to other customers. The proper exercise of this function demands that the banker should be wholly detached from the concern whose credit or securities are under consideration. His decision to grant or to withhold credit, to purchase or not to purchase securities, involves passing judgment on the efficiency of the management or the soundness of the enterprise; and he ought not to occupy a position where in so doing he is passing judgment on himself. Of course detachment does not imply lack of knowledge. The banker should act only with full knowledge, just as a lawyer should act only with full knowledge. The banker who undertakes to make loans to or purchase securities from a railroad for sale to his other customers ought to have as full knowledge of its affairs as does its legal adviser. But the banker should not be, in any sense, his own client. He should not, in the capacity of banker, pass judgment upon the wisdom of his own plans or acts as railroad man.

Such a detached attitude on the part of the banker is demanded also in the interest of his other customers—the purchasers of corporate securities. The investment banker stands toward a large part of his customers in a position of trust, which should be fully recognized. The small investors, particularly the women, who are holding an ever-increasing proportion of our corporate securities, commonly buy on the recommendation of their bankers. The small investors do not, and in most cases cannot, ascertain for themselves the facts on which to base a proper judgment as to the soundness of securities offered. And even if these investors were furnished with the facts, they lack the business experience essential to forming a proper judgment. Such investors need and are entitled to have the bankers' advice, and obviously their unbiased advice; and the advice cannot be unbiased where the banker, as part of the corporation's management, has participated in the creation of the securities which are the subject of sale to the investor.

Is it conceivable that the great house of Morgan would have aided in providing the New Haven with the hundreds of millions so unwisely expended, if its judgment had not been clouded by participation in the New Haven's management?

Go to the next chapter.

Return to the table of contents.