From ROTC to Peace Studies - Russell Vandenbroucke

“From ROTC to Peace Studies”

PeaceDay 2017, University of Louisville Red Barn, 21 Sept. 2017

Russell Vandenbroucke

Listening to the speakers before me, especially Dr. Dawson-Edwards, reminds me of a saying by Carol Hanish from my time in college: “The person is political and the political is personal.” In this context, “political” does not mean partisan, left and right or Democrat and Republican. Rather, it means that our private and public lives are intertwined to echo each other.

“Life can only be lived forward, but it can only be understood backward.” I’m quoting Kierkegaard. In the next few minutes I will do both

We started the evening with a video focused on the United Nation’s International Day of Peace. On the screen beside me is a picture of Kofi Annan, former Secretary General of the UN and one of my favorite quotes, “Education is, quite simply, peacebuilding by another name. It is the most effective form of defesne spending there is."

This day is being celebrated around the world, but through a quirk of history, on this day in1963, the War Resisters League organized the first U.S. protest against Vietnam War with a demonstration at the U.S. Mission to--yes--the United Nations. Two months later, President Kennedy was assassinated. I was in high school. Believe it or not, I was once your age.

If you've seen any of the current Ken Burns documentary on Vietnam playing every night on public television, you've learned something of my generation and my college experience. One of the easiest ways to find a person who opposes war is to talk with a group of soldiers who have actually experienced war. I am not one of them, and in the next few minutes I will explain why.

In 1967, while I was a freshman in college, Dr. King gave what some, including me, believe was the bravest speech of his life: “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence.” He called our government the greatest purveyor of violence in the world and strongly voiced his opposition to the Vietnam war. His was not the path I was on. Nor was the country:

- The next day, 168 newspapers came out against him.

- 75% of Americans opposed his position.

- 55% of African Americans opposed it.

- A total of more than 58,000 Americans would die in Vietnam, more than three-quarters of them AFTER Dr. King moved beyond silence.

- Oh, and over 3 million Vietnamese died too.

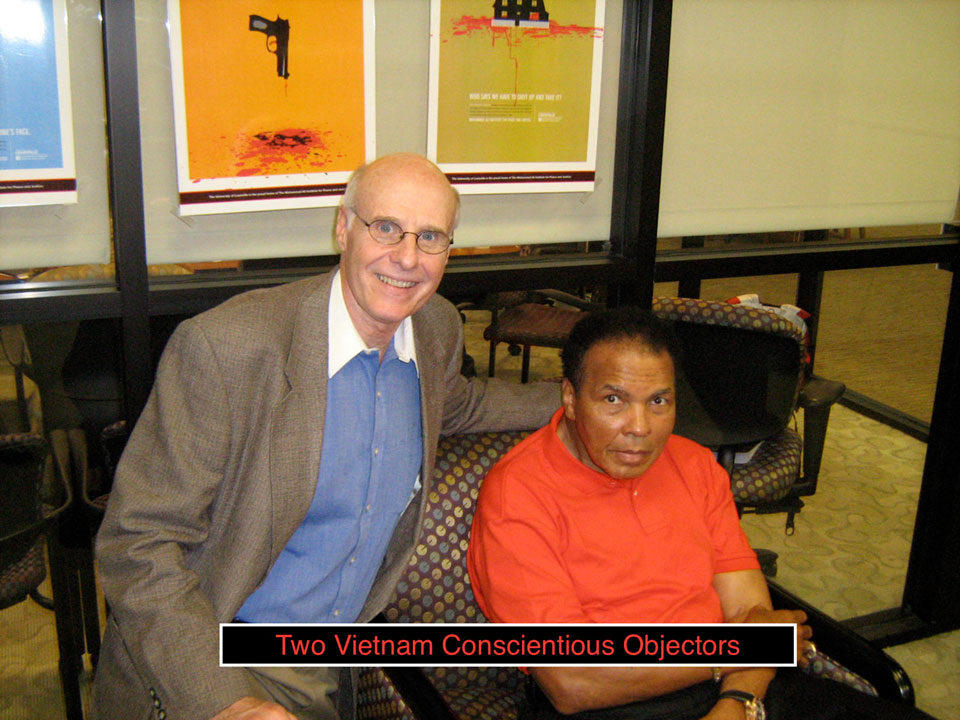

Later the same month as Dr. King's speech, April 1967, Mohammad Ali refused the draft. Instead of considering Ali innocent until proven guilty, the public condemned him immediately. He was stripped of his title before any trial and thereby lost his means of making a living: To support himself, he gave talks on college campuses. This was not the path I was on.

A year later, in the middle of my sophomore year, I decided that since I was going to be drafted after college anyway, I might as well join ROTC and become an officer. Asked during my interview if I would go to Vietnam, I replied that I knew there was a lot of objection to this war but, yes, I would go. I was accepted into ROTC.

That April, Dr. King was assassinated.

And that June, Robert Kennedy was assassinated.

And that summer . . . I went to Fort Benning, Georgia, for six-weeks of training intended to make up for my late start. This was the path I ran.

I remember vividly a late-night display of shells, mortars, artillery explosions, and airplanes dropping bombs and firing mighty projectiles. It was the longest and most expensive fireworks display I have ever seen. And--like those here during Thunder over Louisville--was intended to inspire patriotism, wonder, and awe.

This was the path I was on.

Until one night, after dinner, when the drill sergeant took us out behind the barracks, where we sat on the Georgia soil as he lectured us about chemical and biological warfare. We learned about chlorine and mustard gas. They were used in the First World War to burn the eyes and choke the lungs of soldiers. He told us about anthrax and botulism, and before he was done, he said, "Some of you may be wondering about the Geneva Conventions against chemical and biological weapons. It's true, Geneva prohibis them. But the U.S. Senate never ratified those conventions so we can have 'em. And we do."

In that moment, I knew that the path I was on, was not the right path.

I caught mono at Fort Benning, and was released after 28 days. I left: with an Army shirt that had my surname above the pocket, spelled properly too, which isn't easy; with the metal ring from a hand grenade I was taught to throw in a spiral, like a football; and with the certainty that I did not belong in the military

After drawing #44 in the first draft lottery a year later, I submitted my application to be classified a conscientious objector--that's the name for a person who refuses to bear arms in the military for reasons of conscience. I learned from the Ken Burns Vietnam documentary last night that 500,000 men--all men back then--applied for C.O. status. A year later, my draft board affirmed my claim, which led to me being--thanks again to Ken Burns tabulation--one of 170,000 C.O.’s who performed two years of "alternative service" instead of the military, years spent contributing "to the national health, safety, and interest." I was among the last of these since only months after I finished that service, the U.S. withdrew at last from Vietnam, more than a decade after we started and seven years after Dr. King broke silence against that war.

I was slow to find my path. I had not heard or read Dr. King's exhortation about the war.

I would not have supported Muhammad Ali's refusal of the draft if I was even paying attention to it.

I did not then read the paper or keep up with the news.

College was helping me become a critical thinker, but I focused on the books I was expected to read. I did not apply that same critical thinking to society as a whole or to decisions made on my behalf by my government.

But for that sergeant's talk on chemical and biological warfare, I might have marched long and hard, without thinking whatsoever.

And I might, therefore, have contributed directly to the circle of violence: of one act of violence leading to another and that to another and that to still another ad infinitum.

And I might not have seen, instead, the power of every individual to change the world around us and make it a better place for all of us to live. This is what we have heard and learned from the students speaking before me tonight. They have thought harder and sooner than I did when I was their age.

I end with the words of Margaret Mead, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.