Sarah Oesterly

Greetings from Peru!

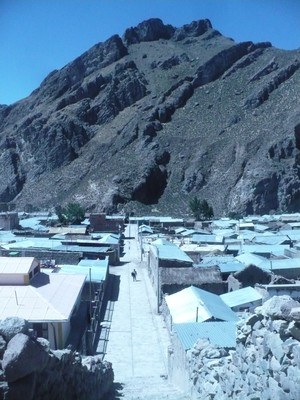

I have been here in Arequipa, Peru for a month and a half now and am glad to say I've finally begun to get into the second stage of the project for which I received the Fulbright Research Grant. Just outside of Arequipa (the second largest city in Peru) is the Colca Valley; you can arrive in about four hours by bus. One of the towns, or distritos, in the Valley is named Tuti. It is a small town, I believe I read there may be approximately 300 residents, and predominately agricultural. In the center of town, in the Municipal Building, a room has been provided to house the town's own Cultural and Historical Museum. My aim is to mount the first exhibition in the museum, showing aspects of local history and culture, local landmarks and even crafts.

What excited me about this project was the chance to work on the process of installing an exhibit from the beginning. I have studied fine arts, art history and anthropology, so I felt like the opportunity to work in a community-based museum, showing cultural and historical features of the town would be a perfect fit. At the same time, I understand that as a community museum in a small town, this project carries a lot of responsibility. After reading a couple of books recommended to me, including Archaeological Museums in Latin America and Cannibal Tours and Glass Boxes, I was reminded that how I, as an outsider, approach the representation of this community's culture is extremely important. The best community museums involve the local community in organization and presentation. Only in that way will the community feel like the museum is a place they can enter and enjoy, something that they value as part of their hometown.

To include local traditions, I have been talking with the senora of the home where I have been staying in Tuti and other women in the community, asking about stories and history of the town. I have been given the names of a few abuelos, older residents of Tuti, who will be able to tell me about the history and the importance of certain sites. For example, there are caves in the side of the mountain called in Quechua quolcas, where they used to store different grains and plants. There are also remnants of Inka inspired buildings and a colonial church in the old part of town on the other side of the mountain from where Tuti is currently located. (The population was relocated around 1570, in the Spaniards efforts to control and indoctrinate the local population). What I hope is to present in the museum exhibition a mix of oral tradition from the current residents of Tuti and data collected by historians and anthropologists/archaeologists.

It has been so interesting to live between two worlds: metropolitan Arequipa and rural Tuti. I spend one week in the city, working on the computer for research, designs, and getting government paperwork in order, and every other week in Tuti talking with the people and, eventually, installing the exhibit. In Arequipa, there is constant traffic and you have to get a combi (mini bus) or taxi to get around. But there is also a big variety of restaurants, from typical Peruvian food (mainly a type of steak or chicken, rice, salad, and french fries), to Italian restaurants like Pesto, and even a couple of American franchises like Burger King and Pizza Hut. It was funny realizing that if you didn't want pickles on your Whopper, you didn't ask them to take off pepinos, in Spanish; instead, the teenagers confirm that you want "No peek-les?" (pickles). There are several anthropological museums with mummies collected from different cultures in Southern Peru, like the Chiribaya, and a surprisingly nice contemporary art museum.

By contrast, Tuti is very tranquil. The first afternoon I arrived, I went to the entrance of the town, to the lookout over the deep river valley, and realized that I didn't hear any music or cars, only the sound of the cascade of water way on the other side of town. The majority of the people have various chacras, or small plots of land, dispersed around town. Some are 30 minutes to an hour away, walking, while some pastures where cows and llamas are kept are higher up and may take all day to go and come back before nightfall. Night, by the way, starts about 6pm, and due to the heavy winds and intense cold that comes right when the sun goes down, the majority of people stay inside or close by after 6. Which is good, plenty of time to read or listen to music and catch up on sleep! During the day, the sun is bright and you should wear a hat and bring lipstick if you don't want to burn or chap (I know, I am still recovering).

The colors of the Valley are breathtaking, and the mountains that line either side of the town and the highway lining the Valley seem close enough to touch. I started a drawing of one peak, and hope to finish a painting of it, but I don't know if even then I could capture the ochres, bright greens and turquoise sky.

The colors of the Valley are breathtaking, and the mountains that line either side of the town and the highway lining the Valley seem close enough to touch. I started a drawing of one peak, and hope to finish a painting of it, but I don't know if even then I could capture the ochres, bright greens and turquoise sky.

Some days I spend in town, waiting to make meetings or getting to know others in the town, and other days I follow my senora to her chacras. We are in irrigation time, so my senora has gone various times to her fields to wait for others t0 be finished with the water so she can open a canal leading to her own fields. The senora is sixty years old and wears the traditional dress (skirts called polleras, the long-sleeved shirt and vest all covered in embroidery, and a white straw hat indicating she is of Collagua heritage). I've seen her pack her lunch in a shawl and tie it over her back, and then walk an hour to her fields, all the while weaving a sweater for her husband. the she will nimbly climb over the stone walls encircling her fields or the dam where water is kept and keep on going. She is impressive! She laughed when I helped her carry the shawl, or when I offered to help turn the wheel to stop water from leaving the dam at night. But I think that my efforts to 'be there' has made her open up to me a little. She never had children, so she jokes that I have become a grown daughter to her.

Although it is hard at times to know whether I am progressing on time with my project, I am reminded that I must just continue working the best I can and allow myself to adapt to the time schedule of those who live here in Peru, both in the city and in the Valley. I am here to learn and contribute, not to impose. I think that has been a great lesson for me professionally and personally. (Did I mention I was also recently married? Respecting another culture is nothing compared to respecting your partner!)

My mother wrote me not long ago to boost my spirits and included a quote from Ruth Benedict: "The purpose of anthropology is to make the world safe for human differences". In reading over the future of anthropology, and what the anthropologist's role should be as we distance ourselves from imperialist perspectives and towards allowing our subject cultures to participate in the telling of their own stories, I find Benedict's quote a comforting reminder of what I believe to be the importance of anthropology: we are here to maintain connection between cultures, to serve as translators of languages, knowledge and customs that allow distinct groups to better understand each other. And with that understanding it is expected that cultures can negotiate better in constructing businesses, communication and ways of life that are beneficial to both. I respect the practical application of anthropological research, and with fingers crossed, hope that my small contribution to the development of Tuti's museum will have a practical effect on the development of cultural programs, education and even tourism in the community.

I will be here in Arequipa until at least June 2011, and maybe later.

Take care!

Sarah Oesterly